The subject of Ed Harris’ movie, Pollock from 2000 is the life of the abstract expressionist, an artistic celebrity of American audiences, whose reputation captured Hollywood’s imagination. It presents (with a nod toward the general public), more or less known personalities of postwar art in the United States: Peggy Guggenheim, Lee Krasner and Clement Greenberg in the typical stylizations of a large format film with a regular distribution. The presentation of the emotionally tormented artist and his studio work on the scene of New York galleries and institutions is predictably simplified. What is interesting to us, however, are the carefully construed studio scenes, based on the photographic documentation by Hans Namuth, which integrally defined the way we perceive Pollock’s work process. Photography becomes the foundation of knowledge, the only truly credible source of information. Taryn Simon, another popular American art world celebrity whose photographic work is always tightly bound to text, says in an interview that we are no longer able to trust written information missing pictorial evidence. Ingrid Shaffner, in her book Wall Text describing the historical role of text in a museum environment, claims the opposite: we see what we are told. Both opinions meet at a single junction: Today, it is irrelevant whether Pollock created his canvases always in a horizontal position in an ecstatic dance of expressive gestures and movements: what matters is that the photographs tell us how such a process looked when it took place.

Dušan Záhoranský and Florian Slotawa jointly examine various perspectives of the relationship between the artist and his studio, the process and outcome, the implementation and its model, references and foundation, in an intimate working environment. While Florian presents a direct link between an artist and a place, Dušan perceives the feedback to the environment through historical works and their destinies. The confrontation of the white cube of Drdova Gallery and the raw industrial space of the Center for Contemporary Arts, with its constant dynamic changes / confrontations between two spaces on the opposite sides of the city, offers a further extension of their analysis.

The Žižkov Monument, based on the winning design by Jan Zázvorka and Jan Gillar of the 1925 architectural and sculptural competition, was predated by two competition rounds in 1913 and 1923 that were never realized, despite many high quality proposals. The First World War swept the 1913 competition off the table, and in 1923, no designs passed muster to translate the sketches and designs into reality. The lengthy selection process and the bloody war interval between the competitions delivered a blow to fine design and to the courage and avant-garde enthusiasm that resonated so loudly in the 1913 competition. The modernist tendencies touching on architectural cubism in the designs of Pavel Janák, Otto Guttfreund, Bedřich Feuerstein, Otakar Švec and Josef Gočár palpably radiate the energy to present new atypical sculptural and spatial forms. The same is true of the designs of Jan Kotěra and Jan Štursa, presenting dynamic figures in motion resembling the deconstruction of a filmstrip, not dissimilar to a year younger Nude, Descending a Staircase, No. 2 by Marcel Duchamp. The same is true of the designs of Vlastislav Hoffman and Ladislav Beneš, whose mass compositions evoke the centre of theosophism, Goetheanum in Dornach, Switzerland. The same is true of the mystical monumental building/sculpture by Josip Plečnik.

The designs of the 1920s are tempered and realistic, often utilizing the structure and morphology of historical styles, leading up to the winning classicist stylized design of a giant, larger-than-life equestrian statue by sculptor Bohumil Kafka.

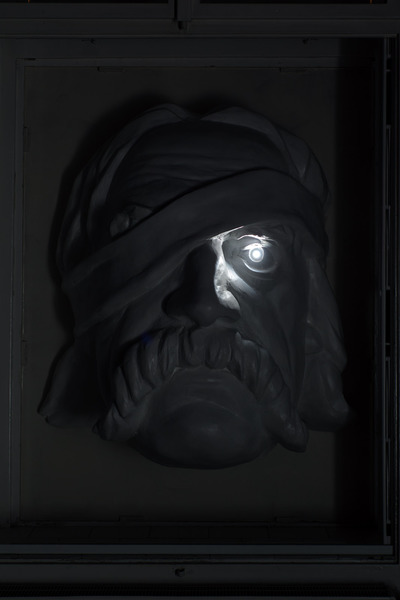

Thus, the nationalistic energy of the rigid order of a new state entity, risen out of the wreckage of the world conflict that left little space for lightness, defeated fine art in sculpture. The Žižkov Monument integrates individual layers of its potential appearance projections, the creative inventiveness of two generations of artists, and two altogether different historical periods separated by a decade that forever transformed the political, social and cultural climate in all of Europe. Dušan analyses the selected individual layers, using sculptures and installations (typical of his own work), creating fictional narratives of the alternative forms of the Memorial through the tension between the sculpture and its movement in time by referring to film and the static photographic image, and the tension between the documentary and fictional ideological projection that materializes in space. He shows the image of the possible as the evidence of the actual present reality beneath the surface of a wholly different final form. In linearly constructed parallel timelines, he reaches the point where he combines a fragment of Kafka’s realized statue and the gallery space and its surroundings, achieving all this with the light of the camera obscura principle. The classical character of the white cube gallery works as a presentational inter-step between a studio and a public space; hence their synergy in the projection of the synergy of individual content layers through something as ostensibly trivial as natural outdoor light.

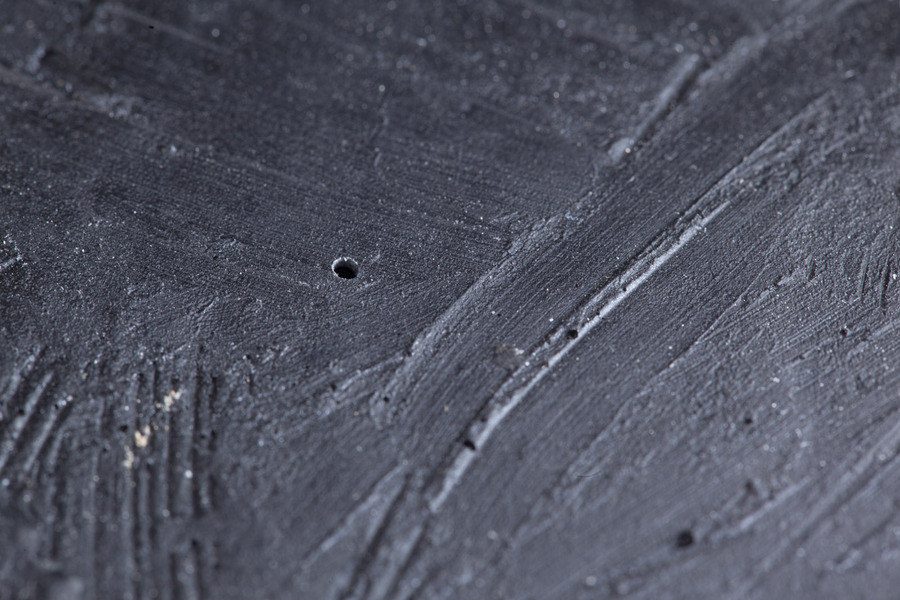

Florian’s photos represent in his philosophy the character of a landscape, a creative space dismissing the relationship between the interior and exterior since both are interconnected. A studio, as an artificial space, thus acquires natural qualities, commensurate with views of nature. It is a specific area with a clear function, which, by gradual transformation, becomes deformed and thrown off balance. The emptied views offer the unseen background of a photo camera, behind which there is the construction all subjects, objects, artworks and instruments that would otherwise remain in the frame. For each shot, Florian rearranged the studio to capture nothing but the empty shell. To an extent, it is an inversion of his previous photography project: in hotel rooms in varied locations (including Prague’s Hotel Europe) he painstakingly composed the deconstructed elements of the hotel’s fixed and moveable equipment. In the illusion of compactness in time, the images offer a progressive dynamic transformation, an imperceptible reconfiguration of the studio. The series can thus be considered a documentation of a performance that takes place away from the camera’s eye, with the artist spending long days of hard labour to produce a single image. The element of temporality and seemingly insignificant labour are essential here, without ever being presented. The new configuration of the pictures in the former bakery, now the Centre for Contemporary Art in Prague, shows again a possible view through Florian’s studio, using the inserted fragments of the deconstructed white cube with sculptural character. This time, it also suggests a reflection of the rest of the space that does not participate in the pictures’ installation. It seemingly merely forms the background with the character of the contemporary pop aesthetics of the post-industrial exhibition space, yet it clearly defines the context of the pictures’ creation. A cleanroom for photographs against an untreated, raw, processual background.

The phrase, I Could Have Just Set It On Fire, almost sounds like something from a David Bowie song. Yet, it may be the simple sigh of an artist. A sigh over an unrealized design, and wasted time and energy. Boris Groys, in his recent text, The Art of Truth describes the transformation of the artist’s position with the advent of our digital age, when the virtual space is the natural channel of art distribution. He mentions an André Breton anecdote about a French poet, who every night before going to sleep hung a card on his doorknob that read: “Silence, please. The artist is at work.” Breton’s story sums up the concept of creative work away from the public, in isolation, where the world has no chance to witness the creative process. A separation from one’s surroundings seems nearly impossible today, what with the relentless virtual and real social confrontation across the international space of the art world. The artist’s work has become a public domain. Furthermore, thanks to the social networks, everyone has become an artist of a kind, as Hito Steyerl often laments. Dušan’s and Florian’s work shows the opposite side of our era, going back in time to more traditional formats. Although their work is just another stop in a continuous process, they demonstrate by their physical presence in the gallery a determination to overcome that sigh in the exhibition’s title.

Curator Jen Kratochvil