“I attended lessons, yes, but only to later dismantle them, strip them and extract solely the concepts that could be of use to me.”

Already the name of the author of ‘The Art of Joy’ – Goliarda Sapienza – promises wisdom, but one that is irreverent, carefree and bohemian. Modesta – our main character – keeps this promise: a resourceful woman, she acquires a brand of wisdom that borders on spiritual heroism. Her determination and desire to emancipate herself from any societal expectations while constructing her own models is delivered without much fuss – as if it were obvious and self-evident that we should follow her example.

“The harm lies in the words which tradition presents as absolute in the distorted meanings those words continue to hold. The word ‘love’ is a lie just like the word ‘death’. Many words lied, almost all of them lied. That was what I had to do: study words exactly as one studies plants animals … And then wipe away the mould, free them from the deposits of centuries of tradition, invent new ones and above all discard and no longer use those that common practice most often adopts, the most corrupt ones.”

We accompany Modesta on a quest to achieve personal liberation, often initiated through sensual or sexual encounters with an ease that makes her transgressive desire seem unremarkable if not ordinary. At times stoic, calculated and ruthless, we admire her from a distance, until she reels us in through intimate and poetic moments and an honesty so blunt that it borders on naivety. Cunningly manoeuvring through life, she attains the benefits of marriage: a title, wealth and a cover for her escapades; resulting in freedom without loneliness, money without work and sexual encounters as she pleases.

“And so for the first time in my life, fui amata amando, I loved and was loved in return, as the aria goes. Something so rare that even now I can recall the feeling of lightness that made me open my eyes in the morning, secure in the new adventure that was born from our embrace.”

Her lovers – of various social milieus, political orientations, professions and genders – not only teach her about a variety of sensual dynamics, pleasure and amorous arrangements but are also chosen for their potential to school her in radical thinking. In a first step she sheds her religious beliefs, to then lay first philosophical and political foundations through her aristocratic in-law’s library, before undergoing a socialist and anarchist apprenticeship via a family friend and lover, to then enjoy a brief encounter with poetry and ultimately become herself a writer and political speaker. Simultaneously Modesta gathers an elective family around her, that functions as a tribe, where children and grown-ups alike are let run free and empowered to strive for knowledge, experience and autonomy.

“And in this present that we’ve had – and have – you’ve given me happiness, taught me new concepts, made me grow mentally”

Sexuality and desire sustain Modesta’s task of creating her own utopia and in so doing reveal a necessity for a sexual, sensual and perhaps even vulgar dimension to utopian thinking. Because desire is not of this world: our heroine – who is both a saint and a murderer – uses her desire to enter into another world, namely that one she desires – her desire in this sense initiates her in a radically foreign existence, because to desire is to believe in the transcendence of the world suggested by the Other – to quote René Girard.

“Love is not a miracle, Carlo, it’s an art, a skill, a mental and physical exercise of the mind and of the senses like any other. Like playing an instrument, dancing or woodworking.’

‘You’re talking about sex.’

‘But isn’t sex love? Love and sex are two sides of the same coin. What is love without sex? The veneration of a statue, of a Madonna. What is sex without love? Nothing more than a clash of genital organs.”

And if desire is not merely what we want, but rather to want what the Other wants, why not emulate Modesta? Marry cunningly. Be an anarchist. Fight the Fascists. Create your tribe. Fuck and love unapologetically. Practice the Art of Joy.

“A revolution through fairy tales! It’s a nice idea, though.”

Nina Beier’s carefully combined materials and objects push them into both a formal and contextual dialogue that reveals cultural codes and the collapse of the systems they represent by laying bare the economical and interpersonal structures at work. A sensually shaped sink is stuffed with a hand-rolled cigar. Heavily loaded with references – phallic vs. curvaceous, manual vs. industrial, cleansing vs. contaminating, tradition vs. modernization, these domestic objects achieve a sensuality and elasticity of meaning in their rearrangement. A glove fixed in the gesture of crossed fingers, signalling hopes and wishes but also deceit, carries badges of commercial, military and religious origin. The pins and tokens, often worn by outcasts, represent a mix of societal powers at work; the glove flaunts the seemingly oxymoronic necessity to believe and denounce in order to subvert. Two wigs, made of natural hair of Asian women, are transformed into haircuts popular in the Western context – neatly arranged and framed, they become an image of the woman that was, will be and wants to be.

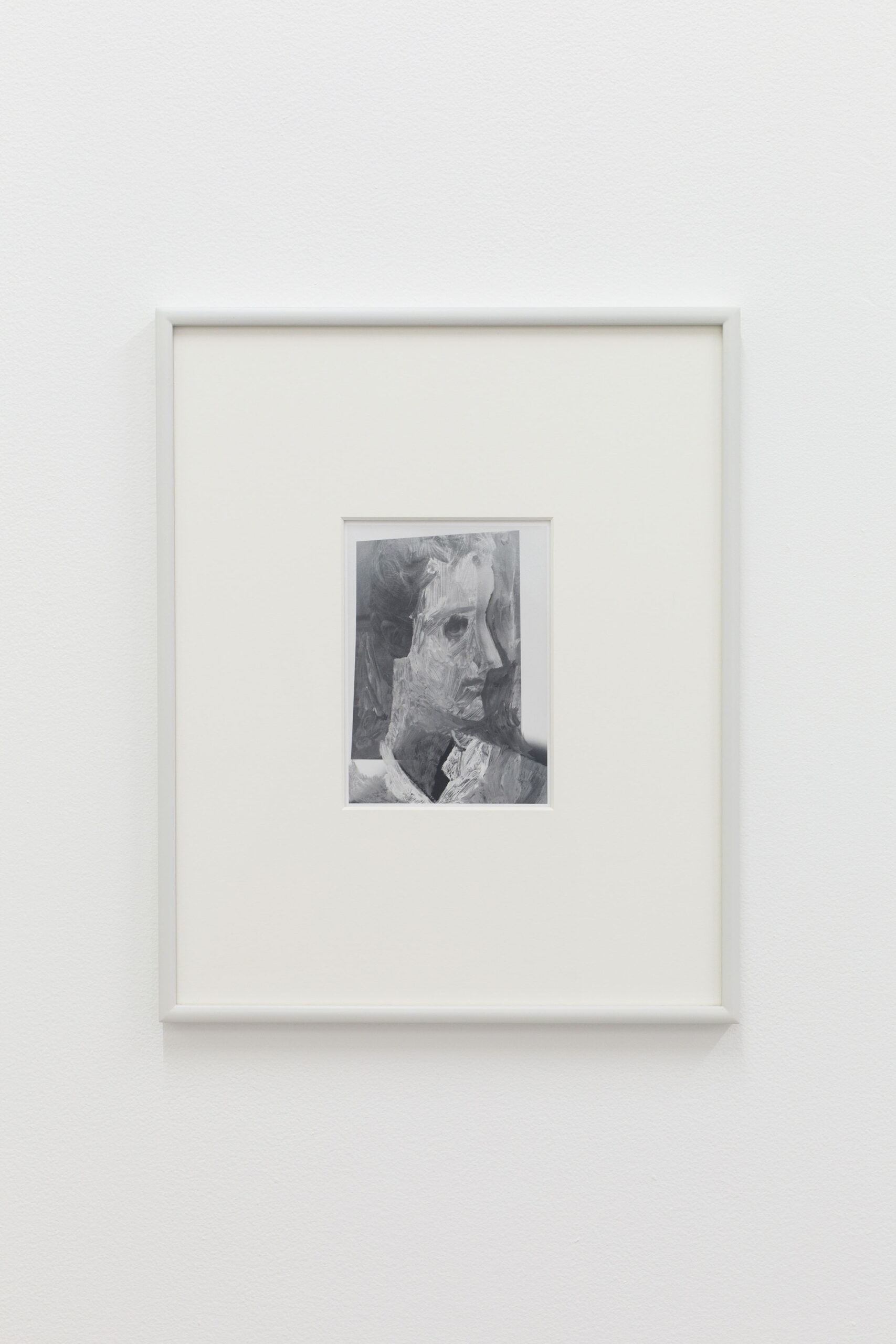

Kazuna Taguchi works her way from image clippings and constructs the female figure at her own discretion. The result is then painted or drawn, which in turn is photographed and carefully manipulated in the darkroom to find its final expression in a photographic print. The merger of sourced reproductions, drawn textures and photographed surfaces simulates a realism that stands in direct opposition to the history of portraiture, since this persona never did nor ever will exist. Taguchi’s approach is subtle and considerate: by not existing, the portrayed women reveal themselves as masks of those who might exist, entrancing us in their ghostly existence of womanhood.

Dino Zrnec furnishes an entire room with carefully arranged carpets into a sensually collaged soft landscape. Some pieces are repurposed leftovers from the factory they were produced at, while the centrepiece is the result of a process of cautious mutual exchange between workers and the artist that required on the one hand the acquisition of knowledge in order to understand the production process and on the other the adaptation of long-established manufacturing methods into unusual ways. Woven from both sides, two images become one. Traces of one side reveal themselves as tender additions on the other, confounding the usual logics of top and bottom.

Romana Drdova’s large scale silk prints feature bold sexual motifs, playful shapes and angry captions. They tell the tale of a painful process of coming to terms with deception, loss and hurt in what seemed to be love. Turning around the dynamics of victimization, pain becomes fuel for creation. Because it is not only benevolent and generous lovers that we learn from and it is also rage, anger and violence that spurs our emotional growth and ultimately allows for catharsis and new love to enter our lives.

Ida Szigethy starts painting in the early 60’s as an autodidact. After the death of her mother she embarks on a self-exploratory painterly series devoted to reconfiguring her identity as a woman. ‘Equation with two bathtubs’ belongs to this series. Naive in appearance, the painting depicts a naked woman lying in bed. Framed by a decorative interior rich with patterns and details, she is flanked by an unusual bathroom featuring not one but two bathtubs, suggesting the absence or expectation of another while projecting confident self-sufficiency.

Kiki Kogelnik shows an eroticism that is seemingly devoid of any emotions – bodies become parts – making us consider the mechanisms of corporeal sensuality but perhaps also the sexuality of machines. An artist unimpressed by what her peers were doing or what was fashionable to her contemporaries, she took pleasure in developing her own iconography, using bold colours and playfully deliberating on love, life and sexuality in an age where the body is clearly already governed by techne.

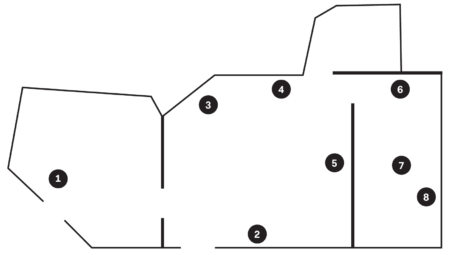

in the beginning

1 Nina Beier

Fingers Crossed Crossed Fingers, 2019

in the living room

2 Romana Drdova

I am not humiliated. Do not be afraid you will not be put to shame. Do not fear disgrace You will no longer remember the shame and the sorrows, 2020

3 Nina Beier

Plug, 2019

Plug, 2020

Plug, 2019

Plug, 2020

4 Kiki Kogelnik

Untitled (Female Figure), 1964

Untitled (Still Life with Body Parts), 1964

Untitled (Still Life with Hands), 1964

5 Kazuna Taguchi

the eyes of Eurydice, 2019

in the bedroom

6 Nina Beier

Warm Lowlights Swept Bang, 2015

Long Layered Shag, 2015

7 Dino Zrnec

Untitled, 2019

8 Ida Szigethy

Equation with two bathtubs, 1971