The exhibition is a collaboration with Brussels-based galleries Waldburger Wouters and Damien and The Love Guru and is part of the international contemporary art gallery display Friend of a Friend Prague 2019

Tell me object, what you want …

Earlier this month, Iceland held a funeral for the first glacier lost to global warming; a new iPhone model is expected to be announced in upcoming week, now including new “Siri intelligence” features; but also Kylie Jenner and Kim Kardashian, sisters and two of the most visible global celebrities, released their new perfume set “Lips”.

The first event represents not only the devastating impact of our civilization, but also an effort to care about the nonhuman surroundings. Glaciers are conceived and mediatized as distinctive objects not only due to their aesthetics and scale, but also as indicators of otherwise hardly observable yet catastrophic changes to our ecological equilibrium.

One of the new features of the next generation of iPhones resides in the use of deep learning algorithms for archiving, indexing and retrieving your photos according to objects they inhere. The very way we create and handle our photos, the structure of our digitized visual memory, is changing.

Such algorithmic or computational photography essentially knows what you are taking pictures of before you even take them – so that it can enhance the image. In this way, we are moving towards a situation where it is not an image that precedes all sorts of objects we can recognize inside; it is an object that determines and forestalls the image.

Moreover, in respect to archiving and retrieving images, instead of folders and files created by ourselves we are moving towards a system where all images rest one next to another in the cloud. They can be easily processed by algorithms to facilitate our access to the world and its visual representation. (With deep learning cameras, we can easily search for images of anything within our dataset.) And all this is done through the category of objects – be they animals, buildings, sunglasses, or our very faces.

… what you really really want

Speaking of faces I want to turn back for a bit to Kardashian-Jenner collaboration resulting in a new perfume line. While purchasing the fragrance shelled in huge, shiny and unfathomably kitschy lips, you are definitely not getting just another scent. You are buying part of the Kardashian or Jenner aura. You desire the smell and the beauty itself – present at hand, commodified or simply made into an object.

This deliberately dull example gives us the idea that anything we desire is not simply out there – accessible for our sensation or experience. No, we need to make it into an object so that it can be valued, praised, distributed, bought in order for us to fit the (social) status we want to attain or need to preserve.

It could appear that these three events don’t have anything in common. But now we see that they present some changes in the way we look at and act upon the world around us. As many times before, we use the frail category of objects – as if they were simple antipodes of ourselves – the subjects. As if they can cover anything from glaciers, or Notre Dame, to our bodies and identities.

But there are definitely many new ways in which we legitimize and fill the concept of an object. In any historical situation there are conditions of possibility or visibility of something out there (Michel Foucault) to actually be recognized as an object. Global warming, algorithmization and identity (media) appropriation illustrated by these three examples might be the most profound ones, but naturally there are more nuanced ways in which we can tackle these mutations.

Furnish your world

Mark Dion, drawings

Firstly, objects pile up in vast numbers and we need to distinguish and classify them in however a simple and crude way. We need to separate a snowflake from a glacier, new from old, an ordinary friend from a celebrity (and these are just three ways among many, namely differences in scale, time or attraction). We are typological creatures creating other creatures.

Typologies are often done in terms of comparison, observable features and properties, but also utility and value; in this way animals and on the other hand instruments present typical objects. Things that are put under huge classificatory scrutiny – things that we need to identify and place or deal with.

Today it may well be again the animals reminding us of the biggest challenges we face. Not only how to behave in the age of global warming affecting virtually all the species – but also how to invent new ways of cohabitation with and sensitivity towards them (Donna Haraway). On the other hand, it is instruments, gadgets, product and goods that represent not only our desires and total prevalence of consumerist culture – but the aspect of design or invention give us the means of dealing with these issues (speculative design, forensic architecture, Benjamin Bratton).

This may be the first step towards a more democratic relation to objects – to redesign and cultivate them and their typologies not in terms of the present and tradition – but in respect to the future and change – as we may observe in work of Mark Dion.

Worlds in objects

Sharon Van Overmeiren, Another Brick In The Wall

But objects are not simply out there, one next to each other. They intersect, mutate, converge or mold. Not only a fish but also the ocean is a sort of object altogether with the millions of tons of plastic waste.

Therefore, objects always relate to each other in a very intriguing way; they not only inhabit our environments but create them. In art, there has been an analogical development. We have moved from the modernist idea, that there are singular pieces inhabiting neutral exhibition spaces, to the situation where no space is neutral or universal since art always constitutes a specific environment for the viewer.

But artists such as Sharon Van Overmeiren go even deeper to inquire into the ability of objects to double, multiply, get in relations, represent one another. This may be yet another step towards the release of the objects – to acknowledge and liberate their ability to create structures, assemblages, environments and worlds.

Their kind of love

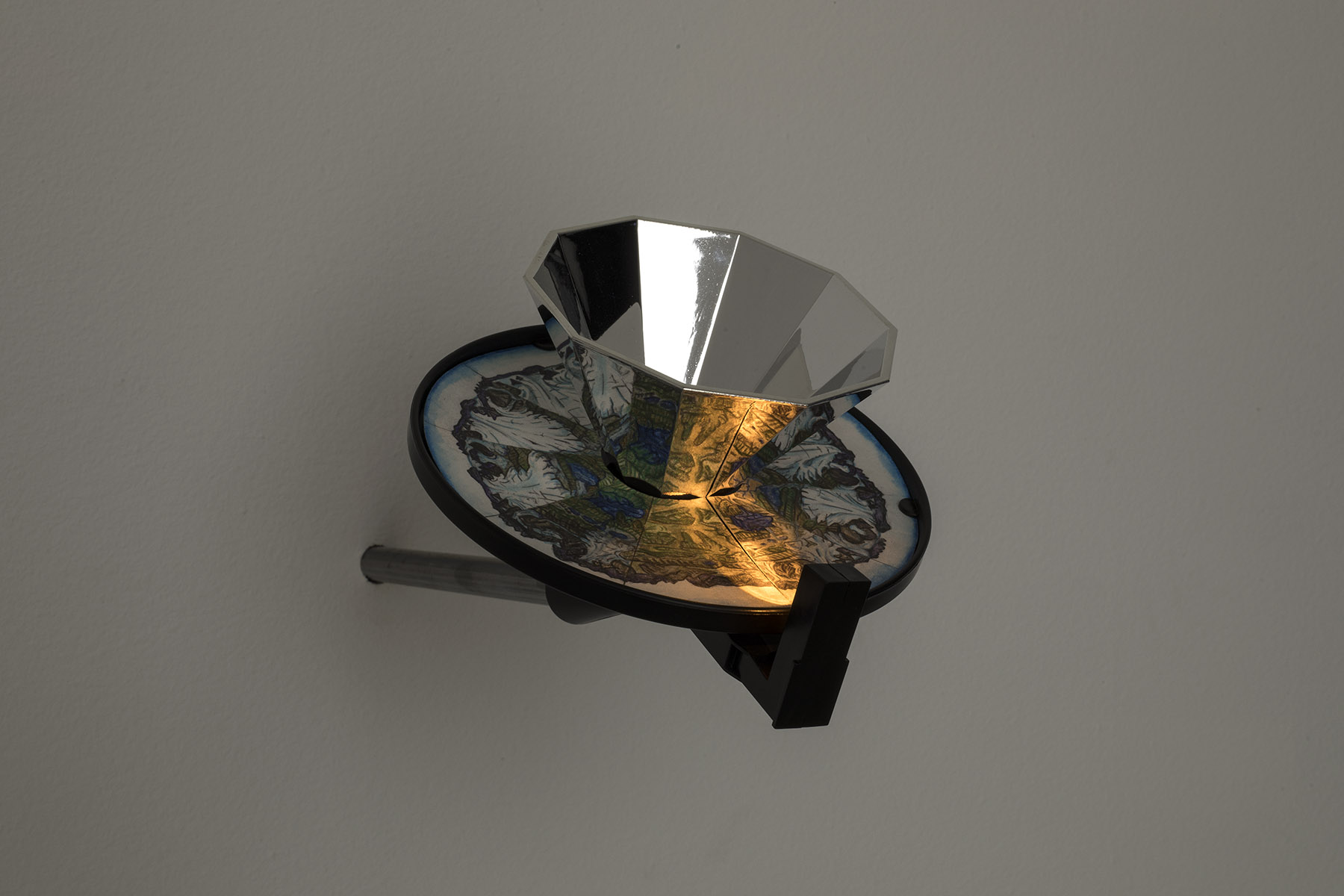

Jasmin Werner, Euro Talisman

While reclaiming their magic-like power to create and cohabit, we are finally moving away from the familiar and human-centered language of visibility, typologies and maybe even the category of object itself. Objects’ ways of inhabiting, acting upon or even forming our common worlds are definitely different, at least to say inhuman. It is more than naïve to think that they feel, communicate or love for the sake of our situation.

Yet there is some sort of affluence or tuning (Timothy Morton). Some sort of invisible yet powerful way to hinge and latch. And here we may form an analogy from the other way around. Maybe it is not objects simply mimicking our anthropocentric ways of living. Maybe it is us humans circulating in invisible or even magic-like loops that we cannot oversee or disentangle. From financial markets and digital clouds, to far more mundane and basic things like affections or imaginations, and climate grief.

This is why Jasmin Werner combines pictures from the European Central Bank with actual Daoist shamanic symbols. As if the power generated by global economics and spiritual diversity operate on a subliminal, incense-like and inhuman level. As if risk analysis, fortune telling or love in a very twisted way come together.

To practice magic means to be susceptible to objects. To be open to their kind of “love” or care.

Care about your object

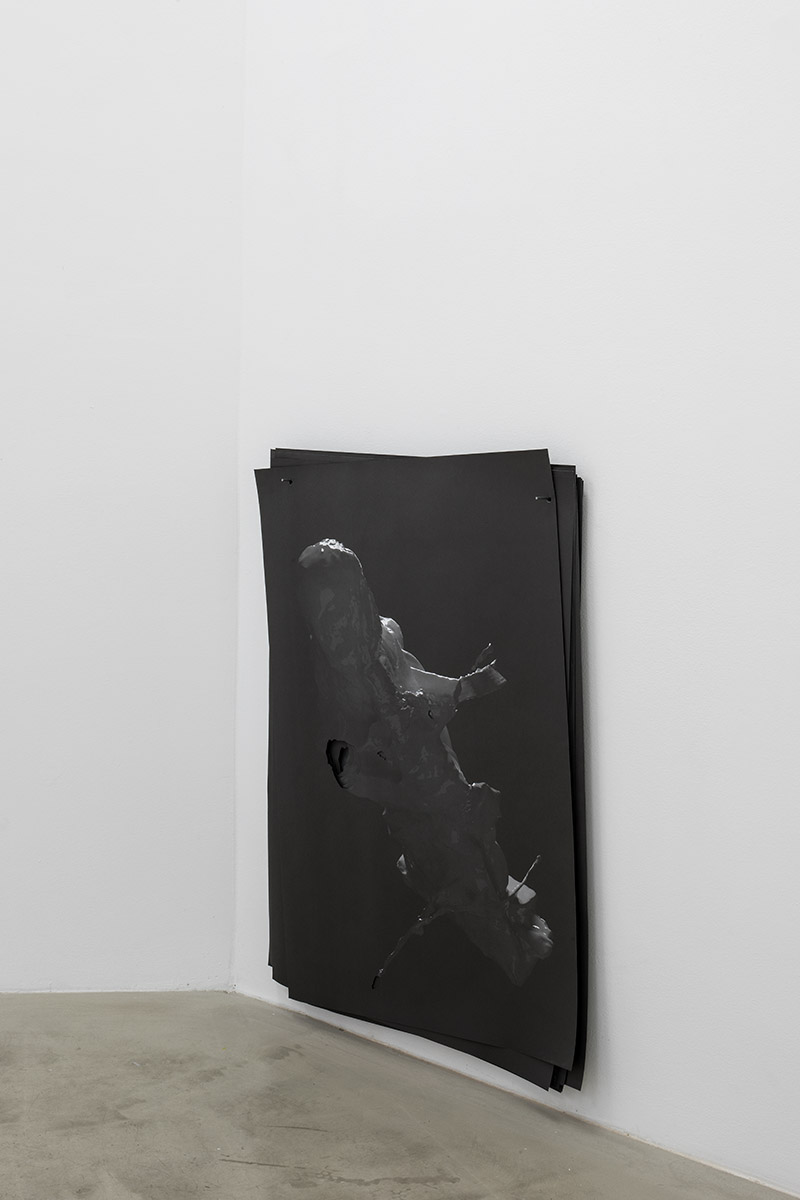

Hynek Alt, Young Day

This is where art comes in. Let’s forget for a moment that art is about artists, their careers or gallerists. Let us assume that art simply presents a very distinctive way to care about objects. But this means not only the art market, (national) heritage or preservation and restoration. It may also inhere the very conception of something as an object.

And it is precisely this process of object-setting (not only its material, form, usage or title, but also delimiting its boundaries, activating it, making it vibrate with meaning or affection) that makes art so deeply relevant and productive. There we can establish or undermine ways in which we label things and make them function.

This may be the reason why Hynek Alt used a plastic cast of Miloš Zet’s sculpture Young Day from the 1960s. It is not only to preserve (both the object or its history); rather, it aims at literally and temporally elevating the sculpture from its context, freeing the object from itself, through dissolution of shape and material, presence and history, sensation and recognition.

Then, to create and curate art means to care, to be always open to new and multiplying ways of relating objects.

Speed and fire

Klara Hobza, Praxinoscopes

Here we see how objects – usually conceived spatially or visually – are embedded in time. They are born, mutate and perish. And we have never (maybe with the exception of our own finitude) been reminded about that fact with such resonance as we are now in the age of climate change, Anthropocene and diverse cataclysmic imaginations.

A receding and returning glacier, a man jumping in and out of a fire, a human face morphing and decomposing again in the prenatal stage of development; these free rather rudimentary images or objects drawn by Klara Hobza immediately open the floodgates of questions about climate crisis, humankind and apocalypse.

Bombarded by media and our own anxiety – it seems like we grew tired of these big problems and questions. Maybe there is no answer anyway. Luckily for the viewers, these three objects are drawn on three praxinoscopes, rotating quickly, over and over; in a similar way as in our media, feeding on the attractiveness and memetic speed of disasters and chance.

In and out

Margarita Maximova, Range Of Clues

Sadly enough, this may be our point of departure, our common condition on our journey to get closer to objects. We both are subject to huge forces of climate, capital or chance. We share a precarious situation with things and environments (Anna Tsing).

Maybe all these forces resonate here and there. Maybe we are just playthings or objects of their will and desire. In this way, they remind me of pulses in the video of Margarita Maximova, where you not only see audio-visual, linear narration but also rhythmic or even tachycardiac pulsation.

It is the rhythm of getting in and out, and therefore a rhythm that entangles us with our environment and its objects.

Love is over

Here in the gallery, there is not much we can do about the forests right now burning in Amazonia, Siberia or Angola and a plethora of other precious objects. But we can still care. We can care about all sorts of issues laying right in front of our anthropocentric ivory hut. Because care is something that must be so deeply cultivated and embroiled; something almost synonymic with culture or the arts.

Maybe you have not read this text and let yourself be dragged through the exhibition from one “object” to another. And I hope that would be even better. But here, I have offered a connection, almost a guide with a few steps in the direction towards objects – retooling our cognition (Dion), assemblaging and generating (Van Overmeiren), activating forces (Werner), care (Alt), acceleration (Hobza) and being devoured (Maximova).

In this way, I hope, it’s not only us being in love with objects (often perverted, commodified or desperate), but it is the other way around.

curator Václav Janoščík